THE TRIAL (1962)

"Nobody else but you could ever have obtained admittance. No one else could enter this door! This door was intended only for you! And now, I'm going to close it."

The Trial (1962), directed by Orson Welles, is one of the great visual artworks of the twentieth century. Adapted from Franz Kafka’s novel of the same name; The Trial is, more than anything, about the endurance of the human spirit and our ability to choose to act either in favour of or against the vague, malevolent, totalitarian demands of a tyrannical power. In essence, it is a tale of individuality which can in and of itself be broken down into three parts. The first is the individual alone. The second is how the individual is confronted by the outside world. The third is how the individual deals with that confrontation.

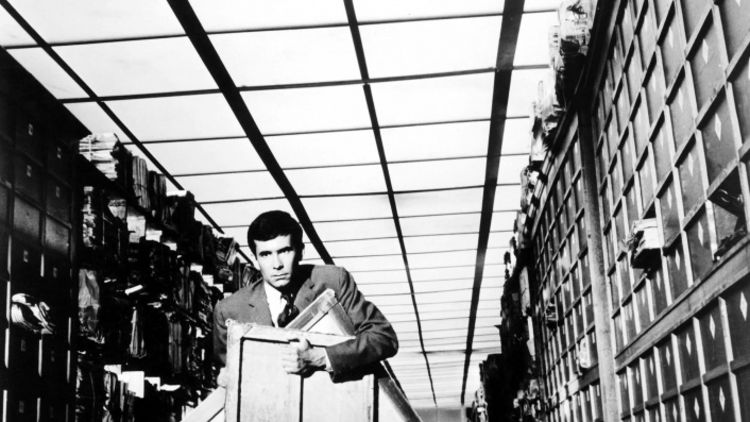

The protagonist of The Trial, Josef K, is someone who starts out relatively naive, but not without a shadow to his ego. As evidence of this, without directly stating it, Welles presents K at the start of the film being accused by the police for an oddly unspecified crime but he is never told what he is being charged with and why. After being introduced as an indefinitely innocent man due to his pleas of innocence - told neurotically in a boyish-yet-slightly-effeminate tone that Anthony Perkins does so convincingly well - a detective stumbles onto a pornograph that K owns in his apartment, at which point K’s assertiveness briefly arises in embarrassment; he confesses suddenly to the ownership of a pornograph and the detective shrugs it off. At this point, Welles makes us aware of the fact that our protagonist isn’t some harmless creature. He is capable of being sinful just like anyone else, and yet we remain certain that he is innocent due to his cluelessness and naivety. And yet, next to all of this, K is a figure who talks back to the detectives when he needs to, and he asks the right questions. We are shown he is capable, flawed and innocent all at once which makes him a likeable and relatable character in the mind of the audience; it serves to sum up the self of the protagonist.

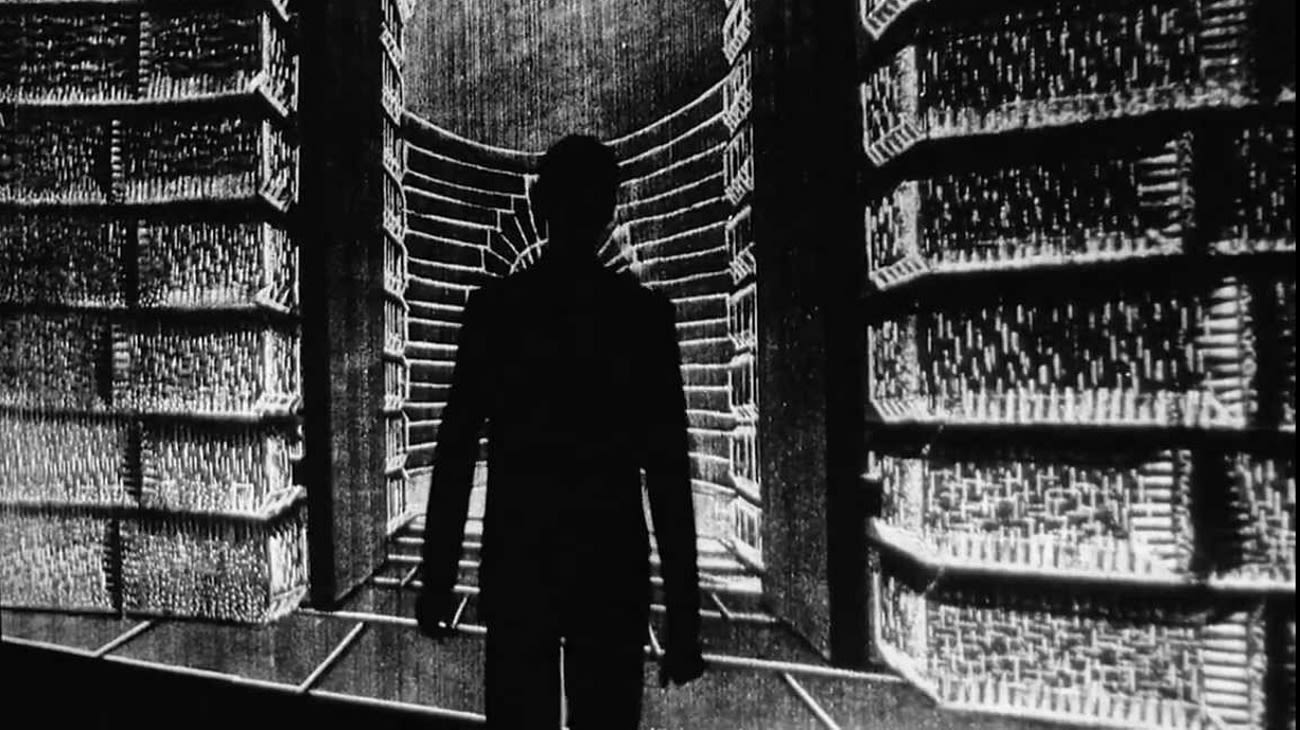

The world of The Trial is a character of its own. Part of the reason why this is the case is because of every corner of every space on the screen is covered with immense industrial detail, thus giving the feeling as if the city itself is alive; air ducts, waterpipes and staircases all serve a part in the anatomical form of the world K encounters. It is a living, breathing, consuming place. There is no moment in which a character goes to a certain location. They are instead placed wherever they are by the world they inhabit and they do not do anything about it due to the tyranny of it all, with the exception of course being K. Welles makes the city imposing by utilising extreme angles as well as wide lenses; along the lines of what Terry Gilliam would much later attempt with films like Brazil (1985) and Twelve Monkeys (1995). The world tries to belittle and subdue K so that he becomes a part of the vague, immoral and rightless law, symbolising the endlessly narcissistic and totalitarian ideologies that find themselves in the extremes of any political side. Kafka seems to have also been aware of the potential for the rise in power of such forces which we today can see coming into fruition. Orson Welles’ character, the Advocate, is the ruler of Hell in The Trial; he is the gatekeeper in the allegory quoted at the start of this essay. He is the ultimate obstacle for K because he refuses to let him metaphorically pass through the door of his own free will by insisting that K has to let him continue working as his lawyer. Politicians repeatedly subdue their citizens in the same way, disallowing them from actually forming a law of their own and instead to act in the interest of the current political agenda.

When a man is confronted with as much chaos as K is in The Trial, there comes a point at which you wish to understand the purpose of it all. In the final act of the film, the Advocate and K meet for the last time in a secluded area of a church where they give lectures and sermons with a projector screen. Orson Welles lights the scene in dramatic fashion, and combines it with intentional pace editing techniques resulting in one of the most memorable experimental sequences in film history. The Advocate uses the projector to explain the aforementioned gatekeeper allegory and it results in the following exchange:

K: “I don't pretend to be a martyr, no.”

Advocate: “Not even a victim of society?”

K: “I am a member of society.”

Advocate: “Do you think you can persuade the court that you're not responsible by reason of lunacy?”

K: “I think that's what the court wants me to believe. Yes, that's the conspiracy: to persuade us all that the whole world is crazy, formless, meaningless, absurd. That's the dirty game. So I've lost my case. What of it? You, you're losing too. It's all lost, lost. So what? Does that sentence the entire universe to lunacy?”

Priest: “Can’t you see anything at all?”

K: “Of course I’m responsible!”

Priest: “My son…”

K: “... I am not your son.”

K establishes his sense of identity in the world. He rejects being a lifelong slave to the system. He is an individual who is bearing the responsibilities and consequences associated with being a free person; spontaneous and detached from the brainwashing tyranny represented by the Advocate and the strict dogmatic practices of the church. K has walked through the door that was meant only for him.

The Trial encompasses what it means to be human in the modern world and what it means to prevail in the face of chaos and totalitarian tyrannies. It is a dark display of the ironic triumph of the human spirit in pursuit of the truth. Truth is obtained by honesty and bearing the responsibility of your own choices. A phenomenal film that serves as proof of the genius of Kafka and Welles alike. It will last in relevance evermore.